Blood Flow Restriction Training Authors: Nicholas M. Licameli (@nicklicameli), DPT & Nicholas Rolnick, DPT (@thehpm) – The BFR PROS (@thebfrpros)

If you’ve landed on this page, you’ve likely already read about how blood flow restriction (BFR) is rapidly growing into the mainstream as both a fitness and rehabilitation tool to accelerate performance & recovery. If not, we encourage you to check out some of the other articles that have been written such as part 1 on devices (here) and part 2 on the science (here).

Now that you’ve armed yourself with the right equipment and know the science, how can you get these gains for yourself? This article will elaborate on exactly WHY and HOW to apply BFR training in practice for a number of different athletes looking to increase their muscle strength, hypertrophy, and cardiovascular capacity to increase performance. At the end of the day – while technologies exist to make BFR training safer than just wrapping BFR bands around your arms/legs, we still should be aware of the potential safety risks when applying what is essentially a tourniquet to our body. Click here to learn a little more about safety before taking the training wheels off and diving into this article.

Here’s what you’re in for – we’re going to tackle some reasoning for why you’d use BFR with powerlifters, bodybuilders, and Olympic weightlifters and then provide some sample programming options for these athletes. A huge portion of whether or not BFR makes sense is understanding why you’re going to do it. Sometimes – BFR makes sense – sometimes it doesn’t. This is why briefly covering the desired adaptations you’re looking to elicit is paramount to just throwing some programming options at you. We’ll then look at programming for cycling/aerobic athletes and offer a couple of different options.

Lastly, since we at BFRtraining.com are some of the leading experts in the world on the topic, we’d be remiss to say this article does not even come close to covering the science nor the diversity of the programming options once you understand the science behind the power of BFR Training! So if you’re interested in learning more, we’ve got a comprehensive reference for you at the end of the article to check out.

Let’s begin…

BFR – NOT IF – WHEN!

Blood Flow Restriction Training for Athletes

BFR Training for Powerlifters

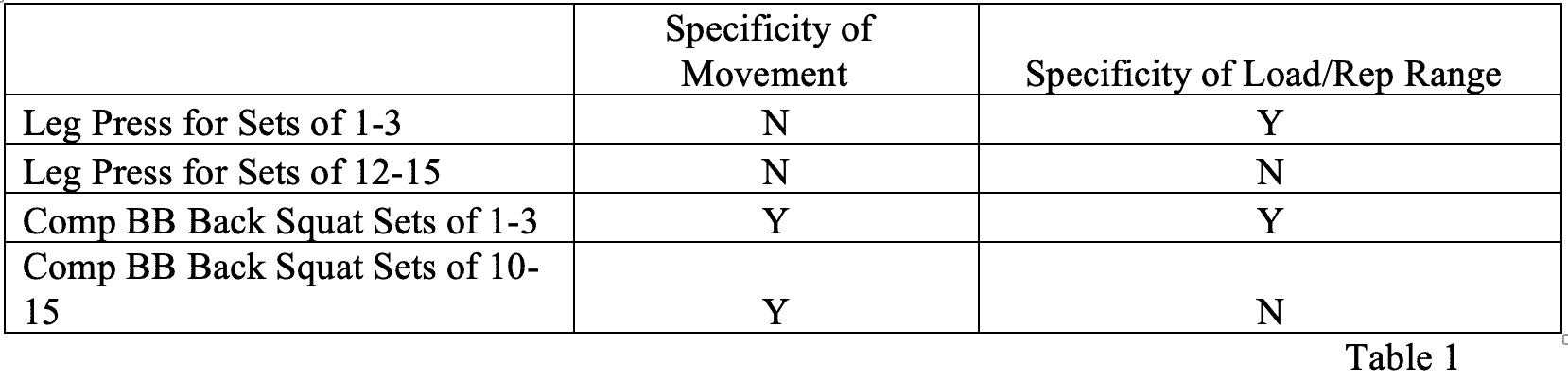

We must remember these three principles of muscular adaptation: variability (stress must be alternated to achieve adaptation), progressive overload (stimulus must progress as adaptation occurs), and specificity (adaptations are specific to the training stimulus). Specificity tends to be key for powerlifters, which means if the goal is to improve the 1-rep max of a competition squat, it is important that heavy competition squatting is included in the training. How then could something like light load BFR ever have a place in a powerlifter’s repertoire? Well, specificity is not quite that restrictive and, as previously mentioned, there must be variability and progressive overload built into a training program along with specificity.

Specificity can be broken down into specificity of movement and specificity of load/rep range. Let’s use our 1-rep max competition squat as an example in Table 1. As you can see, there are viable options to achieve adaptation other than strictly performing heavy squats. This is important because it is not optimal for a powerlifter to only train the same movements with the same reps at the same load. It is typically recommended that powerlifters periodize their training into phases, such as a hypertrophy phase, a strength phase, and a skill/technique phase.

Table 1. Specificity Of Movement and Loading

Hypertrophy phases are important even for a pure strength athlete not only to satisfy the principle of variability but also to improve long-term strength. Components of strength include muscle size, neuromuscular factors like rate coding (efficient muscle fiber recruitment), resiliency and adaptations of muscle/tendon architecture, mood, arousal, and acquired skill. Since muscle size is one of several attributes that make up strength, it becomes more important once the other factors have been optimized. For example, if a seasoned lifter has efficient neuromuscular rate coding, has developed bone, tendon, and muscle adaptive resiliency, is able to tap into proper arousal and mood state and has acquired the proper skill to perform the desired movement, hypertrophy can be quite impactful.

Conversely, hypertrophy becomes less important in a novice lifter since he/she hasn’t yet optimized the other components of strength. It can be concluded that hypertrophy tends to be more important for long-term progress in strength training, especially in advanced athletes who may have “capped out” or are close to “capping out” most other components of strength. Another time when muscle size could be impactful is with movements of low skill level, such as a preacher curl, because there is less of a demand for efficient rate coding, arousal, skill acquisition, etc.

So where can BFR fit into a powerlifter’s training? BFR could be a great addition to a hypertrophy phase because it allows for a drop in load without sacrificing training adaptations. This would allow the lifter to take a break from heavy loads and still reap the hypertrophy benefits of the phase. This type of phase can also be seen as a “load” deload, where intensity and metabolic stress are increased and load is decreased. Varying the training stimulus and giving the joints and soft tissues a break from heavy loading can also be a great way to modulate workload and reduce the risk of overuse injuries.

BFR Training for Bodybuilders

“With respect to the physique athlete, there are numerous avenues for future research that could help elucidate the effectiveness of BFR within this population. There are currently no studies comparing heavy-load resistance training to heavy-load resistance training plus low-load BFR training in highly trained physique athletes nor are there any studies showing the effectiveness of low-load BFR training in maintaining lean body mass during contest preparation.” (Rolnick, 2020)

While the scientific evidence may be lacking, we can still use recent strength training literature to draw conclusions and, through evidence-based decision-making, effectively implement BFR into bodybuilding training. For bodybuilders, the ultimate goals are to build/maintain muscle mass and ensure recovery while slowly and methodically dropping body fat through a combination of diet and cardio. Diet is perhaps the most important factor in maintaining a caloric deficit and eliciting changes in body composition, but optimizing hypertrophy training is absolutely critical as well. With that in mind, BFR may be a useful training method to supplement traditional resistance training and maximize the hypertrophic stimulus.

For bodybuilders, BFR training can be used (1) to assist in achieving the three components of hypertrophy (mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress), (2) during planned deloads, (3) as one of many ways to vary training stress, and (4) to enhance the mind-muscle connection.

(1) The Hypertrophy Trifecta and Recruitment of High Threshold Motor Units

The hypertrophy trifecta of mechanical tension (heavy loading), muscle damage (breaking down muscle tissue), and metabolic stress (cell swelling – the pump) has been hypothesized to positively contribute to maximal increases in muscle growth. One practical way for physique athletes to include BFR into a program would be to add on 1–2 exercises per target muscle group at the end of a traditional non-failure heavy-load training session. This is similar to performing metabolic/oxidative training (tempo work, drop sets, and myo-reps) at the end of a workout. With metabolic/oxidative training, we are creating occlusion within our muscles, increasing fatigue, creating a hypoxic environment, recruiting high threshold motor units, and training our bodies to buffer and clear metabolites.

Remember the trifecta…mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress. Traditional heavy training likely checks the mechanical tension and muscle damage boxes, which is why this type of training is typically foundational to most bodybuilding training programs. However, in order to fully maximize the hypertrophic training response, an athlete should include some training that induces metabolic stress. Metabolic stress training can preferentially stress muscle fibers that may not be sufficiently stressed at higher loading intensities (i.e., type I fibers). The addition of low load BFR to traditional heavy load training could be one way of covering all bases.

It should be noted that simply training to failure would likely check all boxes as well, however, failure training is not always appropriate or feasible especially with heavy compound movements and for physique athletes in the midst of contest preparation. So why even consider using BFR when we could just train to failure? BFR does not compromise recovery to the same extent as traditional failure training and recovery is key, especially when an athlete is in a sustained caloric deficit and at extremely low levels of body fat. Once the repeated bout effect has taken place, we see less muscle damage and soreness following BFR training, which could be a key factor in recovery from training session to training session.

(2) BFR and Deloads

Deloads are crucial for physique athletes who are looking to build and maintain muscle mass while dieting down for a competition. Bodybuilders typically train with medium to high volumes, moderate loads, relatively short rest periods, and at close proximity to failure all while in a caloric deficit and extremely low body fat levels. Similar to powerlifters and as mentioned above, sometimes a deload of load/rep range is necessary for recovery and variation of training. Keep in mind that if an athlete chooses to deload due to general burnout from high-intensity training, BFR is likely not a great option because the intensity and perceived effort is typically higher with this type of training.

(3) BFR as a Way To Vary the Training Stimulus

Varying the training stimulus is not only a principle of muscular adaptation but also a strategy to mitigate the risk of developing overuse injuries. Changing loads, rep ranges, RPE, and exercise selection are all strategies to achieve training variation. When it comes to hypertrophy, athletes have the freedom to explore different loads, rep ranges, and movement patterns while maintaining a hypertrophic response so long as volume and proximity to failure are adequate. BFR is one of many ways to periodize training stress without compromising the hypertrophic stimulus.

(4) BFR and the Mind-Muscle Connection

While we’re not familiar with any scientific literature to support the claim that BFR can improve the mind-muscle connection, anecdotally it seems to be a valid claim. Trainees often report improvements in the ability to “connect with” and “feel” working for muscle groups while training with BFR. What we do have evidence for is the idea that improving the mind-muscle connection could potentially improve our ability to produce a hypertrophic stimulus. Will the mind-muscle connection make or break your gains? Likely not. However, the mind and muscular connections made during BFR training may carry over to free flow training, which over time may have a meaningful impact. If nothing else, for a bodybuilder, “feeling” the muscles being worked makes training more enjoyable and energizing!

BFR Training For Olympic Weight Lifters

We’re finally on to the fine modern gentlemen of the lifting community: Olympic weight lifters. Before getting into specifics of BFR and Olympic weight lifters, it should be noted that across the board, all kinds of strength and physique sport athletes could benefit from the ability of BFR to allow training to proceed in the face of pain or injury. Regardless of the sport, BFR can allow athletes to modify training without sacrificing muscular adaptation.

Olympic weightlifters are required to move heavy loads off the ground, overhead, at rapid speeds, and with precise technique. Due to the fast and explosive nature of the sport, type II muscle fiber recruitment is of utmost importance. As previously mentioned, since both type 1 and type 2 fibers have the ability to produce high amounts of force and contribute to overall hypertrophy, athletes in sports that involve heavy lifting at slow speeds (i.e. bodybuilding and powerlifting) would want to equally develop both type 1 and type 2 fibers.

How Do We Implement BFR into an Existing Strength and Hypertrophy Training Routine?

Now that we have explored some reasons why powerlifters, bodybuilders, and Olympic weightlifters may want to consider using BFR, let’s talk about how to start. Like any novel stimulus, BFR should be introduced at low intensities and gradually progressed to prevent excessive soreness and allow the repeated bout effect to occur. In other words, we need to train. Excessive early BFR training volume may hinder recovery and have a negative effect (at least acutely) on other aspects of training, especially for the powerlifter and Olympic weightlifter where type 2 fiber recruitment is essential for maximal sports performance. Keep the training wheels on the BFR initially!

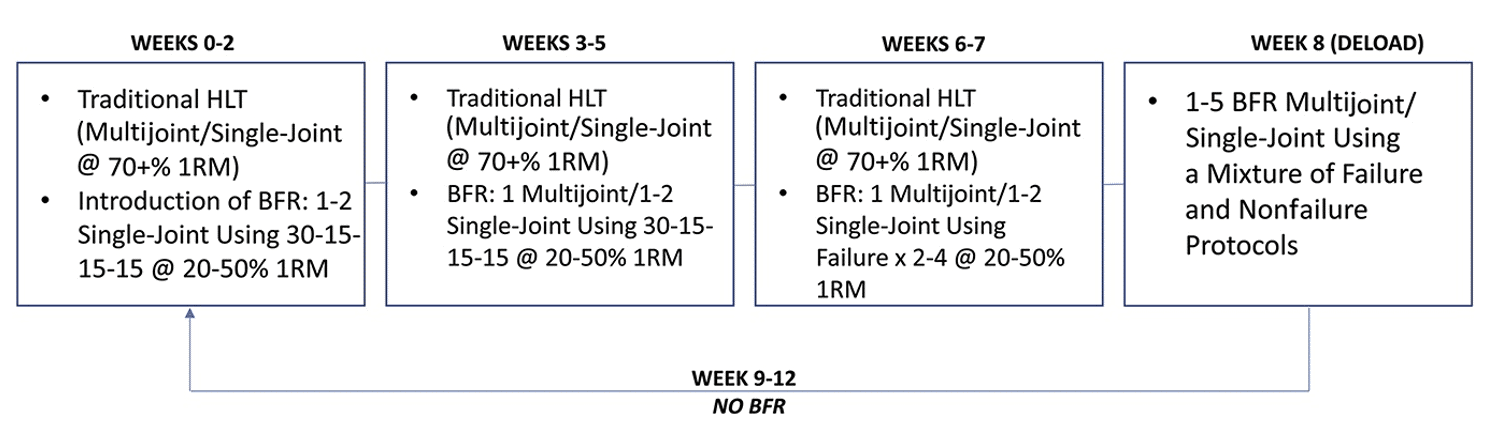

Below is one example of how a bodybuilder might introduce BFR into an existing program, but the same principles can be applied to any athlete where type 2 muscle fiber recruitment is essential to performance enhancement. The table below was taken from Nick Rolnick and Brad Schoenfeld’s 2020 paper titled, Blood Flow Restriction Training and the Physique Athlete: A Practical Research-Based Guide to Maximizing Muscle Size. It can be accessed at this LINK.

Table 2. Example programming of BFR for the Strength Athlete

Throughout the weeks, BFR is used following traditional heavy load training. Weeks 0-2 start with 1-2 sets of non-failure BFR using single-joint exercises. In weeks 3-5 BFR training is progressed to 1 multi-joint movement and 1-2 single-joint movements, still avoiding failure. Weeks 6-7 begin to touch failure and Week 8 uses BFR during a deload from traditional high load training with a mixture of failure and non-failure training. The purpose of this example is not to be prescriptive, but rather to offer a practical example of how to integrate principles into practice.

Pain Modulation and Injury Management

So far we’ve separated powerlifters and bodybuilders as if they were some sort of separate species, but what do they have in common other than a love for the Iron Game? Powerlifters and bodybuilders will all likely feel pain at some point. In fact, it is hard to imagine an athlete going through a career and never experiencing some sort of pain. After all, pain is a normal human sensation just like hunger or thirst. One of BFR’s greatest areas of impact is the management of pain and injury.

First, let’s briefly talk about pain and injury. This is an excerpt from a previous article of mine titled, A Guide to Injury Reduction and Management, which can be accessed right here.

Injuries, like pain, are multifactorial, poorly defined in the scientific literature, extremely variable from activity to activity, and rarely are simply due to a single traumatic tissue-damaging event. One of the most impactful ways to reduce injury lies in our ability to manage the balance between load and capacity…and that is where a qualified healthcare practitioner, like a physical therapist, can help. Workload management is the management of the load we expose ourselves to and our bodies’ capacity to recover from it (see below).

In order to gain a better understanding of how to properly monitor workload, let’s quickly define load and capacity. Load includes physical stress such as miles ran, weight lifted, daily step count, duration of a sporting bout, and gardening/yard work. Capacity is impacted by things like sleep quality/duration, mental stress, anxiety, depression, prior beliefs, expectations, past experiences, illness, training age, muscle strength, endurance, bone density, tendon resilience, skill, coordination, comorbidities that impact recovery such as diabetes, preparedness for a specific activity, and mental resilience.

After ruling out red flags, we approach pain and injury by gradually exposing the body to the edge of discomfort to desensitize the system to the desired movements while maintaining a training effect. It is here where BFR truly shines. The goal is to find a pain-sensitizing variable such as load, volume, RPE, range of motion, exercise selection, sleep quality, stress management, hydration, recovery, etc., then offer modifications to keep the athlete training as close to the desired level as possible. Once we load and train the system with the modifications in place, we slowly progress back to where we want to be, in a stepwise fashion. As we modify training variables, we are likely forced to sacrifice adaptation to some degree. However, BFR helps maintain a training effect while modifying around pain and injury! Basically, it allows us to achieve a minimum effective dosage at volumes, loads, and intensities that would otherwise be insufficient.

Not only can BFR help with training around injuries, it may also have implications in the short-term modulation of pain. There appears to be a pain-reduction effect following a bout of BFR training, which allows for a window of opportunity to use loads that would otherwise reproduce pain. In this instance, BFR becomes a bridge to heavier loading, which in my opinion, is the most significant effect of this training method.

A Word on Ischemic Preconditioning (IPC)

Ischemic Preconditioning (IPC) is a tool that can be used prior to training to potentially improve performance, time to exhaustion, and volume completed, as well as, reduce muscle damage and within-session strength loss. That being said, we are lacking evidence that explores the acute vs. long-term significance of these findings and whether or not impacting the above-mentioned variables actually lead to more weight lifted on the platform or more muscle mass on a physique. The protocols for IPC are typically passive bouts of 5 minutes of complete arterial and venous occlusion followed by 5 minutes of free flow, repeated 3-4 times. The practicality of a passive 40-minute pre-training routine is questionable for most, but the evidence is nonetheless compelling. If it is feasible for a powerlifter or bodybuilder to complete the IPC protocol prior to training, we see no reason not to give it a shot!

BFR and the Aerobic Athlete

I know what you’re thinking… “But wait, not everyone wants to get jacked and strong. Some of us have other goals, like distance running, rowing, and cycling!”

Point well-taken…

Along with its potential benefits for resistance training, BFR has shown some promising results for aerobic training, as well. Most commonly studied are walking and cycling, however, there is research to support its use with jogging, sprinting, and even rowing with collegiate and professional athletes with high levels of VO2max (> 60 ml/kg/min). Gaining and maintaining muscle mass during training can be extremely beneficial for the aerobic athlete. While the improvements in muscle hypertrophy and strength tend to be small and occur in deconditioned and untrained individuals, there may be some potential for well-trained individuals to improve hypertrophy with higher intensities and higher frequencies of BFR endurance training.

We also see increases in aerobic capacity (VO2max) and even anaerobic power in both untrained and well-trained individuals when BFR is used with aerobic training. Finally, there is evidence to support improvements in functional clinical outcomes in the elderly, which are predictors of fall risk, functional mobility, and overall quality of life.

Here’s the best part…those potential benefits can be achieved at lower intensities and durations than endurance training without BFR! With traditional aerobic training, we typically need to train at more than 50% heart rate reserve (HRR) multiple times per week for greater than 10 min, however, with BFR, we see positive adaptations at intensities as low as 30% HRR! Similar to load in resistance training with BFR, there seems to be no benefit to high-intensity cardio with BFR (at least with the cuffs on during exercise…), so be sure to keep the intensity low to moderate with a restriction time of 5-30 min per exercise bout. It is recommended to start with a minimum of 50% LOP in the legs and a minimum of 40% LOP in the arms.

Similar to strength and physique athletes, endurance athletes can also use BFR to deload or train around injury without sacrificing a training effect. As is the case with BFR and resistance training, BFR and aerobic training allow an endurance athlete to achieve a minimum effective dosage at intensities lower than what would typically be required.

How should BFR be integrated into an already existing endurance athlete’s training? Let’s use a cyclist as an example. As with any novel training stimulus, dosage should start low and gradually increase with time and adaptation as the repeated bout effect takes place. There are two ways to program aerobic training for the triathlete/cyclist. The first would be to add it to the last minutes of a regular training program. Heart rate reserve values can be higher to accommodate for increased specificity while LOP can be lower (due to higher exercise intensities). This can serve two purposes. The first – to accommodate the unique stresses of BFR exercise and the second – for providing a “BFR base” for another programming in the future.

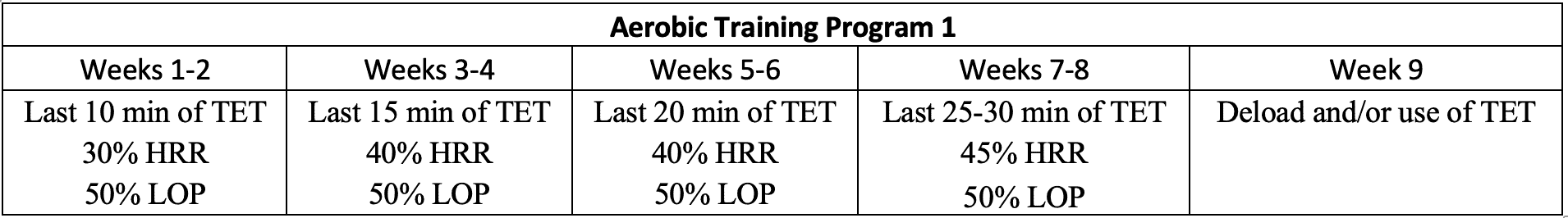

Program 1 Sample BFR Endurance Training Program for Cyclist

Goal: Facilitate increases in VO2max via upregulation of hypoxic tissue responses from increasing duration of ischemic exercise; possible augmentation of muscle hypertrophy and/or strength due to increased local muscular fatigue. Ideal Frequency 3x/week

In Weeks 1-2, we suggest using BFR in the last 10 minutes of traditional endurance training (TET) at 30% HRR with 50% LOP. In Weeks 3-4, the duration would increase to 15 min and the intensity would increase to 40% HRR. In Weeks 5-6, the duration would increase to 20 minutes and the intensity would increase to 50% HRR. In Weeks 7-8, intensity increases further to 45% HRR at a longer duration of time (25-30 minutes). Week 9 consists of traditional endurance training only, with a possible deload depending on the athlete’s goals and timeframe.

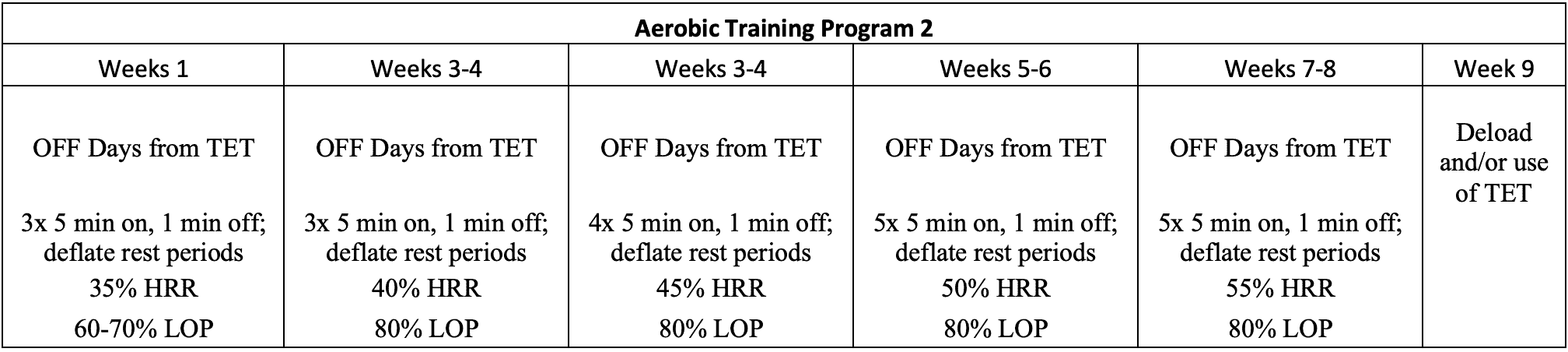

Program 2 Sample BFR Interval Endurance Training Program for Cyclist (Off Days)

Goal: Facilitate increases in angiogenesis via reperfusion to augment VO2max; possible augmentation of muscle hypertrophy and/or strength due to increased local muscular fatigue. Ideal Frequency 3-4x/week

Contrary to Program 1, Program 2 could be integrated as its own separate training day apart from the traditional aerobic volume work. This program will rely on working at slightly higher intensities to take advantage of the ischemia-reperfusion properties of BFR training and increase the stress to the peripheral vasculature. The increased blood flow post-deflation will help provide the stimulus needed to produce new capillary supplies to the working muscles improving local tissue aerobic capacity. Program 2 progresses similarly to Program 1 by gradually increasing the number of intervals of exercise, pressure, and HRR values to maximize intensity (although 55% HRR is still relatively low in the grand scheme of aerobic training intensities). Pressure is increased here as a means to induce further hypoxia and create a greater ischemia-reperfusion response.

Final Note…

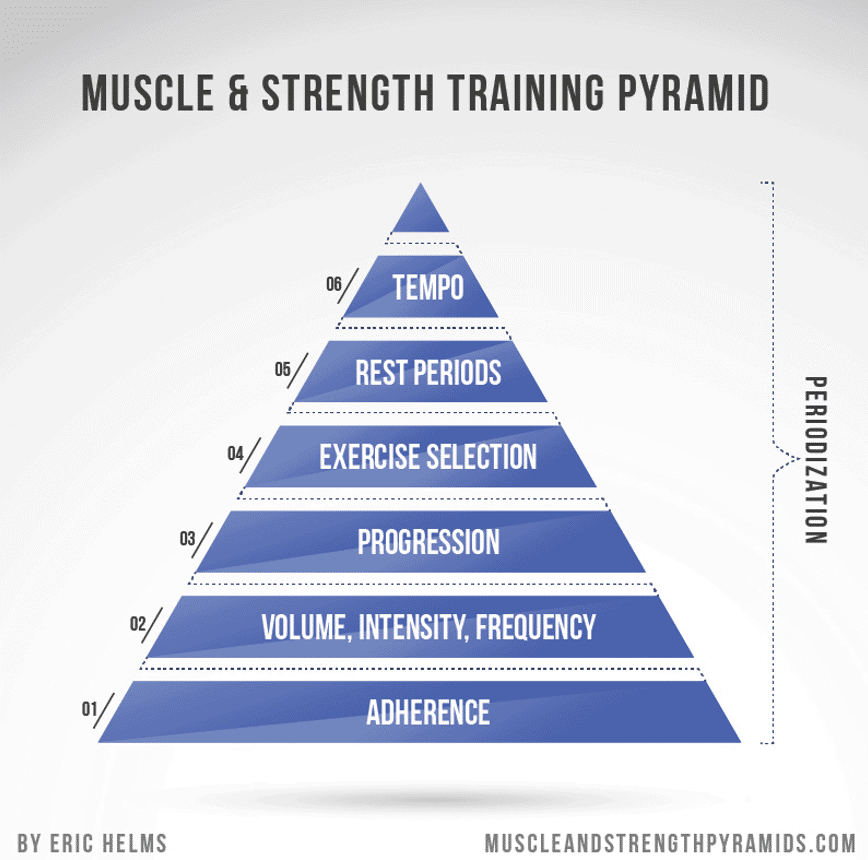

Remember that although this article focuses on BFR training, it should be noted that BFR is simply a method of carrying out principles to enhance our training and create muscular adaptation. As the saying goes, “Methods are many, principles are few…Methods will change, principles never do.” BFR should be considered only after due diligence has been given to adherence, sleep, nutrition, stress management, progressive overload, and recovery. We need to keep things in perspective and remember the order of importance, outlined in Dr. Eric Helms’s Muscle and Strength Pyramids seen below and linked HERE. Do not major in the minors. Focus on the pyramid and be sure the big rocks are in place before turning to things like BFR training. Most importantly, the decision to use BFR, or any training method for that matter, should be based on the pillars of evidence-based practice.

Did this article peak your interest? We’ve got you covered to quench your thirst for more BFR…including more programming and periodization options with protocols ripped directly from the literature. We’ve brought our successful in-person workshop completely online to reach more people and change more lives while growing safe BFR training practices.

Be sure to check out our engaging 4-hour On-Demand On-Line BFR Training course at www.BFRtraining.com if you’re interested in becoming a leader in this rapidly growing area of rehabilitation and fitness.

Our on-demand course is for rehab and fitness professionals and will provide everything you will need to overcome the three hurdles for successful BFR Training and help guide you to become a Confident & Successful BFR Provider.

Click this LINK to get started!

Related Articles: