If you’ve spent any significant time working to push your performance to the next level, you know that an occasional tweak will happen that creates some soreness with exercise. Usually, these tweaks though are nothing to worry about, and training can continue as normal. But what can you do when a more significant injury occurs? After months or years of hard work to improve your performance, you can’t just stop training during this injury. You need to continue training when injured to not only maintain your fitness (strength, hypertrophy, endurance, etc.) but to continue improving in whatever way possible.

Fortunately, some minor changes in your training plan can keep you training without exacerbating tissue healing timelines. Use these tactics as ideas to implement to continue training when injured (not medical advice).

Related Article Series: Best Exercise Variations to Use When Injured:

Five Tactics To Continue Training When Injured

Limit Range of Motion

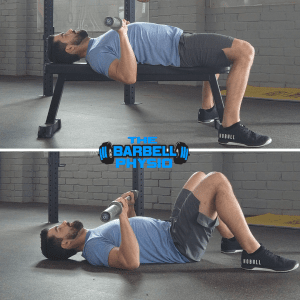

For many muscle and tendon injuries, pain and more damage can happen when the muscle is under tension in a stretched position. So in these conditions, limiting the range of motion can be a great way to continue training hard and heavy without slowing tissue healing. For example, in an athlete that has strained his or her pec muscle limiting the range of motion with an exercise such as a floor press instead of a bench press can often be enough to allow an athlete to push heavy weight without pain.

Deadlifts can be another example of this. Many athletes recovering from low back pain have difficulty pulling a barbell from the ground. But deadlifts are a great exercise to use when rehabbing from back pain. By elevating the bar a few inches off the ground can be a great tactic to continue pulling weight, building strength, and working the hip hinge pattern.

Use Exercise Variations

Small changes in the exercise variation we perform can be another great strategy for continued training when injured. Altering your grip, torso angles, knee positioning, etc. can change the amount of load placed on an injured joint or muscle. Let’s use the squat as an example. The front squat typically has a more upright torso versus the back squat. For many athletes with hip or back pain, this slight change in set up can allow for pain-free training.

View this post on Instagram

For athletes with shoulder pain, subtle changes such as changing your grip angle can have a positive impact. Switching to a neutral grip with a football bar or dumbbells rather than a barbell with exercises like the bench press or overhead press can very quickly change the pain you feel.

Unloaded Irritated Tissues

Sometimes we need to unload a tissue to avoid overstraining it completely. But we can use exercise variations to continue training the surrounding muscles to continue to improve their strength. For example, in someone with low back pain not tolerating compressive loading very well or a post-op shoulder, barbell squat variations may not be possible. The belt squat is one great option to continue loading the legs without risking these healing tissues in other areas.

View this post on Instagram

A banded hip hinge movement is another excellent example of how we can unload the spine while still pushing leg loading. Place a resistance band around the hips to resist hip extension. As the individual becomes more tolerant of spinal loading, they can add external resistance with barbells or dumbbells to challenge the hips and spine while decreasing the band resistance.

Lighten Loads

I know that we all want to train hard and heavy. But at times, we can’t push maximal loads. If we have to lift lighter weights, we simply push up the volume to similar to what we would program in a hypertrophy block. As the injured tissues heal and tolerate heavier loading, we decrease the volume and increase the weight. Here’s an example of how we might progress that over several weeks:

- 1st Week: 3×25

- 2nd Week: 3×20

- 3rd Week: 3×15

- 4th Week: 5×10

- 5th Week: 5×8

- 6th Week: 5×5

Train Contralateral

In extreme situations, an area may not be able to be loaded at all. The best example of this would be after an orthopedic surgery, we frequently have sutures holding tissues together. If overloaded, the repaired tissues will fail, so we have minimal options for training that area.

In this case, we are going to push training the uninjured side as muscle as possible because research has shown that this helps us maintain strength and muscle mass on the injured extremity. While many fear that doing this will create a deficit in side to side strength or muscle mass, the opposite appears correct, we’ll decrease the amount of fitness we lose. Once the healing process progresses, we can begin using some of the above strategies to begin rebuilding fitness.

Note: none of the above should be considered medical advice. Always defer to a licensed medical professional. But, use the above as a guideline for principles to discuss with your medical team. We hope these ideas allow you to continue getting in some positive training when injured.