Top Squat Variations for Training While Injured

Squats are one of the most effective movements for building lower body strength, power, and athleticism. But when you’re dealing with pain—whether it’s in your lower back, hips, or knees—the standard back or front squat can quickly go from a staple lift to a major aggravator. In this article, we’ll break down the best squat variations for training while injured.

Need specific help to rehab your injury? Find an Onward Physical Therapy location near you to team up with a fitness forward physical therapist. Our approach to rehab: Use the Gym, Don’t Leave the Gym!

Belt Squat

The belt squat is one of the most effective ways to train the lower body without placing stress on the spine—or the upper body. By suspending weight from the hips, this variation completely unloads the lower back and upper body, making it an ideal choice for athletes dealing with back pain, shoulder issues, or those who tend to over-rely on their spine during traditional squats.

Because the weight is loaded below the torso, belt squats allow athletes to maintain a more neutral spine while still driving significant stimulus to the quads, hamstrings, and glutes—without taxing the shoulders, elbows, or wrists.

There are several ways to set up a belt squat, but the SquatMax-MD stands out as the most biomechanically sound option. Unlike lever-based machines—which often force lifters into awkward movement patterns—the SquatMax uses a vertical loading path that closely mimics proper squat mechanics. Not only does this reduce injury risk, but it also helps reinforce good technique that will carry over when you return to traditional barbell squatting.

View this post on Instagram

Want more variations like this? Check out [this article] for additional pain-friendly squat options.

Cyclist Squat

The cyclist squat is a front squat variation that’s especially useful for athletes managing lower back or hip pain. By elevating the heels on a slant board or bumper plates and maintaining a front rack barbell position, this variation encourages a highly upright torso throughout the squat.

That upright posture significantly reduces stress on the lower back—making the cyclist squat a smart option for those dealing with back discomfort. It also shifts more of the loading demand onto the quads, providing a solid strength stimulus while easing the burden on irritated joints.

Additionally, the heels-elevated position minimizes hip flexion and anterior hip compression, which can make it more tolerable for athletes dealing with hip impingement or other front-side hip issues.

For best results, we recommend investing in a high-quality slant board to allow for consistent foot positioning and stability.

Safety Squat Bar Squat

The safety squat bar (SSB) squat is a go-to variation for athletes dealing with shoulder pain or limited shoulder mobility. For those who struggle to reach back into a traditional back rack—or who can’t tolerate the front rack due to pain or post-operative restrictions—the SSB provides a smart workaround.

With padded shoulder rests and forward-facing handles, the SSB allows athletes to maintain control of the bar with minimal shoulder involvement. This design significantly reduces strain on the shoulder joint while still allowing for a challenging, balanced squat that targets the lower body effectively.

We recommend the Rep Fitness Safety Squat Bar.

While not all gyms are equipped with a safety squat bar, a simple workaround is to use lifting straps looped around a regular barbell, holding the straps in front of your chest to simulate the SSB grip. This is FAR from a perfect substitute and we don’t recommend doing maximal weights with this set up. But for higher rep work this can be a solid option when equipment is limited.

Hatfield Squat

The Hatfield squat is a unique and highly effective variation that combines the safety squat bar with hand support from a stable surface—such as handles, J-cups, or a rack—positioned in front of the body. This setup minimizes shoulder involvement and enables the athlete to maintain a very upright torso throughout the lift.

The upright positioning not only reduces stress on the lower back but also allows athletes to move heavy loads while placing a greater emphasis on leg strength and hypertrophy. The hand support adds an element of stability, making it an excellent option for those recovering from injury or looking to push volume without taxing the spine.

Invented by legendary lifter Dr. Fred Hatfield (aka Dr. Squat), this variation is a hidden gem that deserves more attention—both in rehab settings and for athletes chasing serious lower body gains.

Read our full Hatfield Squat guide.

Zombie Squats & Strapped Front Squats

If wrist or elbow pain makes the traditional front rack position unbearable, zombie squats and strapped front squats offer two excellent workarounds.

In a zombie squat, the bar rests on the front of the shoulders without being held by the hands. Instead, the arms are extended straight out in front of the body for balance. While this removes stress from the wrists and elbows, it also dramatically increases the challenge of stabilizing the bar—often making the upper back and shoulders the limiting factor rather than the legs.

To improve load stability while still protecting the wrists, a better option for many athletes is the strapped front squat. By looping lifting straps around the bar and holding them in front of the chest, athletes can maintain a solid rack position without needing full wrist or elbow mobility.

For an even more secure setup, we recommend using Versa Hooks by VersaLifts. These provide a strong, stable alternative to traditional straps and allow athletes to maintain excellent bar control with zero stress on the wrists.

Box Squat

The box squat is a classic variation used by powerlifters and strength coaches to build maximal strength—but it’s also an excellent tool for training around pain.

For athletes with knee pain, the box squat offers a unique advantage: by cueing a more hips-back movement and encouraging a vertical shin angle, it reduces stress on the knee joint. This makes it a highly effective short-term modification for staying active without aggravating symptoms.

It’s important to clarify that forward knee travel is not inherently dangerous. While allowing the knees to move forward slightly increases knee stress, it actually reduces stress on the hips and low back. So, this isn’t a long-term “fix,” but rather a temporary adjustment to manage pain while maintaining lower body training.

The box squat also proves useful for athletes with hip pain—particularly those experiencing symptoms like hip impingement or a “pinch” at the bottom of a standard squat. By adjusting box height, you can limit squat depth to avoid painful ranges while still reinforcing the squat pattern.

Spanish Squat

The Spanish squat is a lesser-known but incredibly effective variation—both as a squat accessory and a pain-friendly alternative for athletes managing injuries.

In this variation, a thick resistance band is anchored behind the knees, pulling the athlete slightly forward as they descend into a squat. The key cue here is to maintain a vertical shin position throughout the movement. As the athlete stands, the band resists knee extension, keeping constant tension on the quads.

Because the Spanish squat places minimal load on the spine and doesn’t require holding external weights, it’s a great option for athletes with back pain. And thanks to the vertical shin angle, it can also be more tolerable for those with knee pain—all while providing a surprisingly intense quad stimulus.

This variation is especially useful as a supplemental movement to build quad strength, reinforce squat mechanics, and maintain training volume when more traditional lifts aren’t an option.

Sissy Squat

The sissy squat is a bodyweight-only variation that delivers a surprisingly intense stimulus to the quads—without loading the spine or hips.

In this movement, the athlete keeps the hips extended, rises onto their toes, and drives the knees forward while leaning back into the descent. This positioning removes virtually all load from the lower back and minimizes anterior hip compression, making it a great choice for athletes who can’t tolerate traditional hip or spinal loading.

The exaggerated knees-over-toes position challenges the quads through a deep range of motion, building strength and resilience in a pattern that’s often undertrained. Whether used as a primary squat alternative during injury or as a supplemental movement, the sissy squat is a powerful tool for lower body development when traditional squats aren’t an option.

The Band Sissy Squat is a similar variation that keeps the hips and low back unloaded while providing a killer quad stimulus.

Conclusion: Working Out While Injured

Pain doesn’t have to stop your progress.

Whether you’re dealing with back, hip, or knee issues, the squat pattern can—and should—still be part of your training. The key is knowing how to modify your approach. By selecting the right squat variation, you can continue building strength, preserving movement patterns, and maintaining your fitness without aggravating your symptoms.

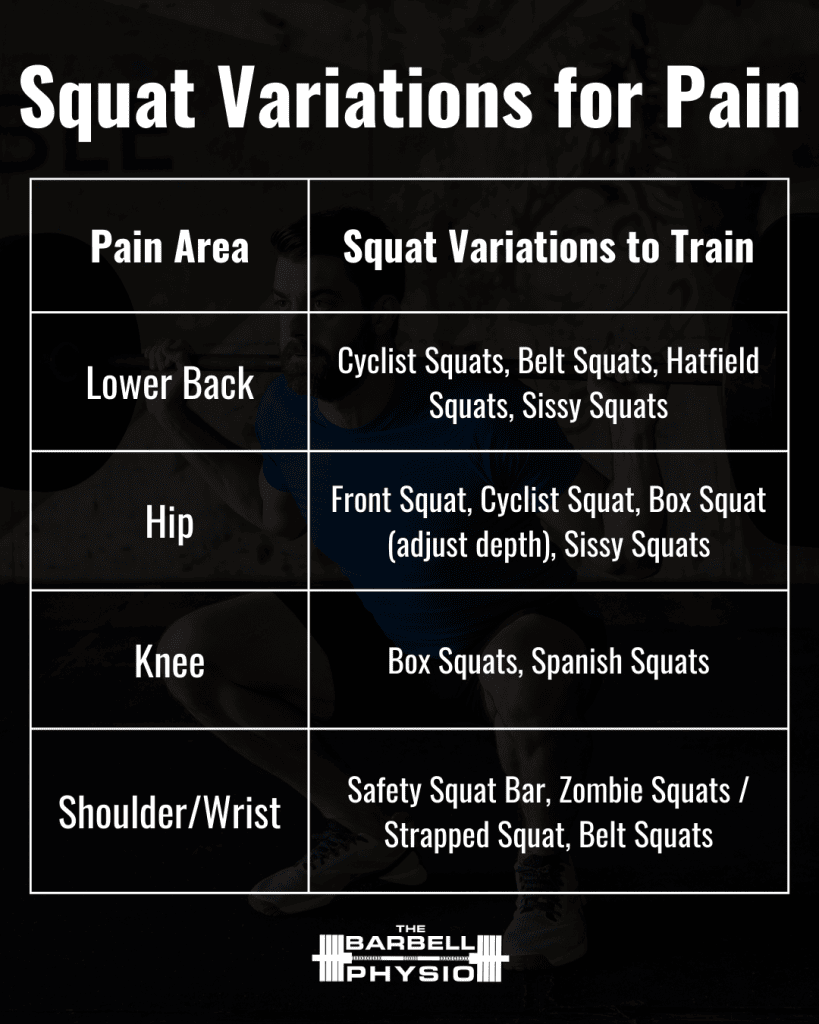

Here’s a quick-reference guide to help you choose the best variation based on your needs. For individualized rehab guidance from fitness forward clinicians, find an Onward Physical Therapy location near you!