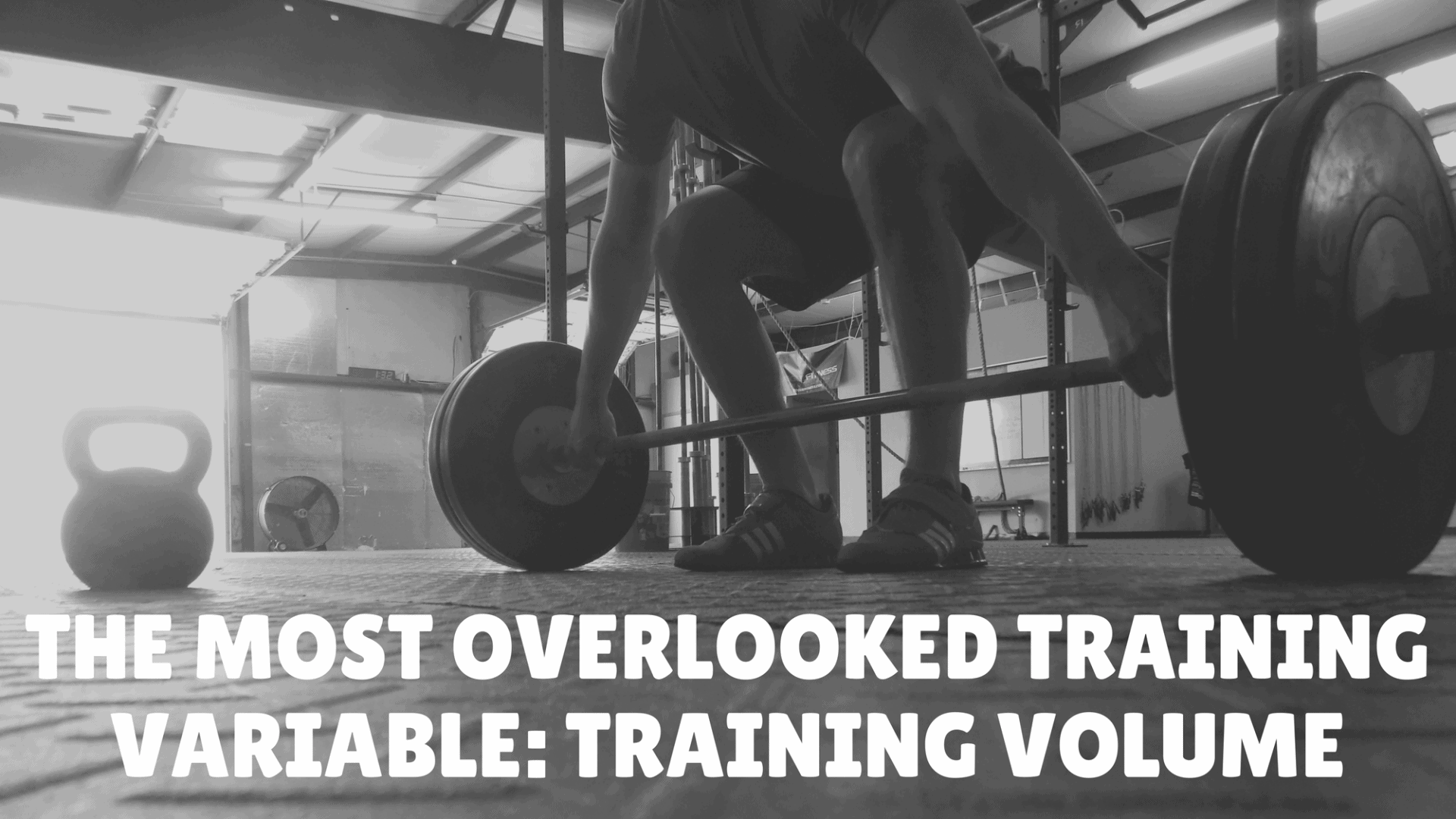

The Most Overlooked Training Variable: Training Volume

When athletes exercise or coaches program training plans, there is no lack of attention to sets, reps, variation in exercises, and providing sufficient stimulus for adaptations to occur. But the most overlooked training variable I see both from a performance standpoint, and an injury factor is training volume.

Often athletes will blame their mobility for injuries. They will think that improper nutrition is preventing muscle growth. But RARELY do athletes or coaches stop to wonder if they are doing TOO MUCH volume to allow for optimal health and performance.

To examine this, let us first define some terms (kudos to Dr. Mike Israetel and Dr. Tim Gabbet for much of the following).

Training Volume Terms

The following graph outlines the various amounts of training volume we can have. We must first be at or above the MINIMUM EFFECTIVE DOSE that will provide positive stimuli. Failure to be at this level will result in no adaptations. BUT it is also important to note that this is the volume that will produce the smallest amount of positive adaptations.

If we want to optimize our adaptations, we want to reach the MAXIMAL ADAPTIVE VOLUME. This volume is such that performance is improving maximally and the athlete is recovering sufficiently. Here we are TRAINING OPTIMALLY!

Finally, we can reach and exceed our MAXIMAL RECOVERABLE VOLUME. At times passing this is necessary to overload the system and then provide a deload period to allow the athlete to recover and adapt to the demands placed on it.

BUT CONSTANT TRAINING AT OR ABOVE MAXIMAL RECOVERABLE VOLUME IS WHERE INJURIES AND DECLINING PERFORMANCE QUITE OFTEN OCCUR.

(For more see Dr. Mike Israetel)

Another great representation of this concept. We want to be in the Goldie Locks zone, where everything is “just right” to maximize our performance gains while recovering sufficiently and avoiding injuries.

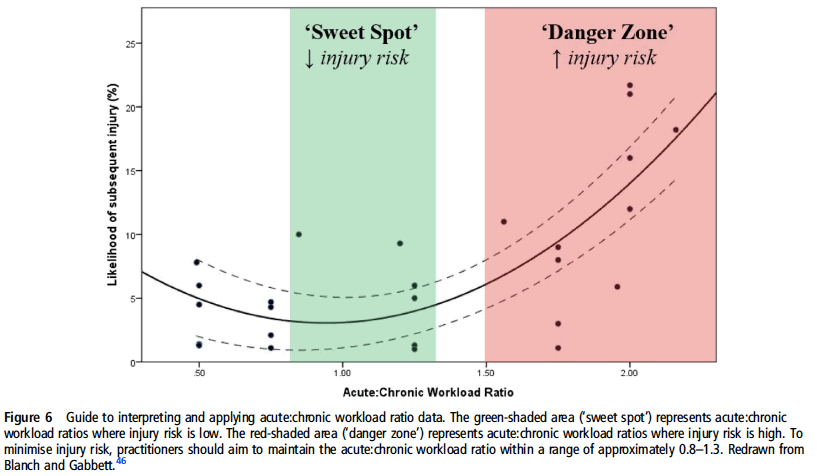

Dr. Tim Gabbett has also performed a significant amount of studies related to training volume, which, when looked at, provides evidence to suggest that training volume may be the most important factor when it comes to injury prevention (sorry mobility and technique fanatics but you just aren’t as important!).

Dr. Gabbett’s work highlights an important concept of the acute to chronic workload ratio. Basically, this is comparing your overall training volume acutely (one week) to chronic loads (four+ weeks). According to his research, we don’t want to see either acute spikes up or down in training volume. A “sweet spot” of 0.8-1.3 was identified as the optimal zone for the acute: chronic workload ratios. When training volume fell outside of this zone, injury risk was increased.

Important note: Dr. Gabebett’s research is on professional athletes at high levels of sport. This research is not universally transferable so I do not regularly do the below calculations. Instead, I use his research as a general rule of thumb. Don’t do too much, too soon. Build slowly.

Okay, So Practically What Does This Mean For Me as an Athlete or Coach?

The point of all of the above is NOT to say we should not train hard, frequently, or heavy. In fact, quite the opposite. We just need to be smart about how he handles training volume.

An athlete’s MAXIMAL RECOVERABLE VOLUME is a changeable variable. As we improve general fitness and address lifestyle influencers on recovery we can continually work on improving work capacity and tolerance to volume.

But with Dr Gabbett’s research in mind, this is done methodically with small increases in volume. Quite frequently in the sports world, the 10-15% per week guideline for training volume increases is used.

Tracking training volume is easier with some sports than others. In the first picture in this article, you’ll see the number of sets performed in reference to maximal recoverable volume. In the bodybuilding work and weight lifting world this makes an easy way to track volume.

But for other athletes, such as CrossFitters, the math to track sets would become much more difficult.

For example, a workout with an RPE of 8/10 performed for 30 minutes would equal 240.

And if an athlete’s RPE based workload for a week totaled to 1000, then we’d want the following week’s total workload to fall between 800 and 1300.

A workload outside of this range would increase an athlete’s risk of injury.

For others, tracking this workload over some time may help them identify how much they actually should be training.

For example, I quite frequently advice CrossFit athletes that seek my help to either

1) take an extra rest day per week OR

2) take one workout per week and just “cruise” by working at a 6/10 vs. 8/10 RPE.

It’s amazing how this simple change has a profound impact on performance and health because we are focused on TRAINING VERSUS A WORKOUT.

What do I mean by that? Well, TRAINING is focused on making gains day in and out to provide the best outcome months and years down the round (sometimes these gains are large, sometimes very small). A WORKOUT is focused solely on an acute stimulus that may or may NOT contribute to long term goals.

For example, a workout so intense that you are sore for a week was a great acute stimulus, but quite often, the decreased performance that comes during the week of soreness counteracts the benefits of the single workout.

TRAIN OPTIMALLY

In summary, this article’s aim is to assist you in training optimally. That level at which your performance is improving to the best of your capabilities without excessive injury risk factors. When your training volume exceeds this maximal recoverable volume, not only will your performance decline slightly due to lack of recovery, but should this lead to an injury requiring the loss of training time, you’ll see significant step backs.

So please take a step back, analyze your training plan, and find your “Goldie Locks Zone.”